Can a sannyasi give diksha to a householder priest according to the scriptures? If not, why is Tunga Mutt doing it in Rameshwaram?”

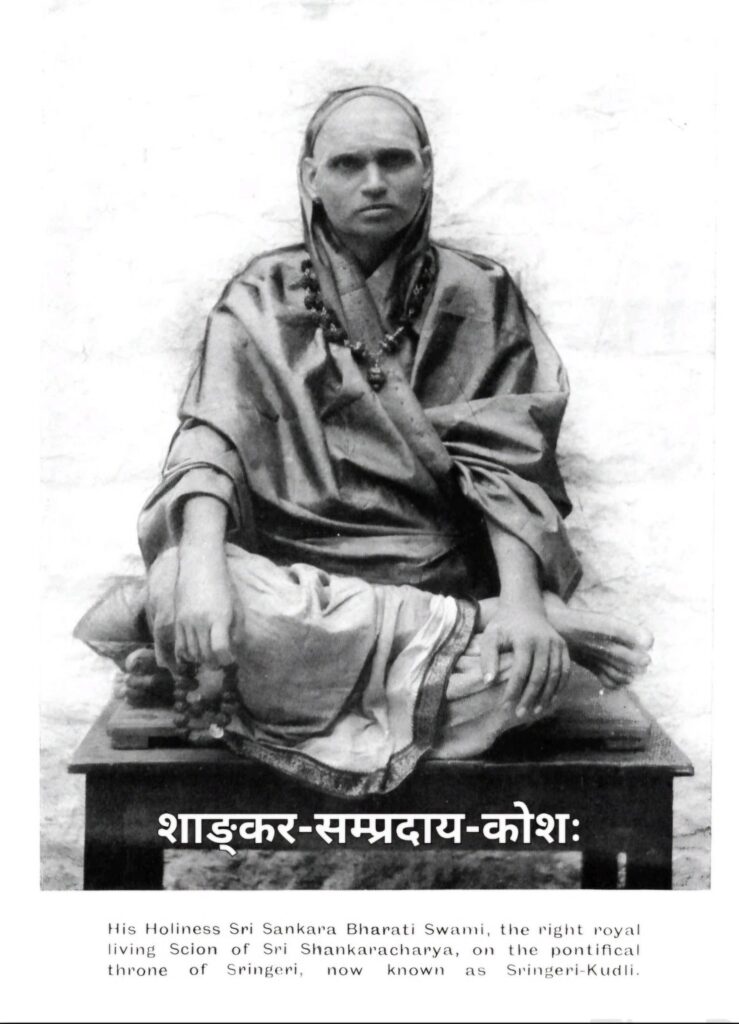

Category: Shankarite Institutions

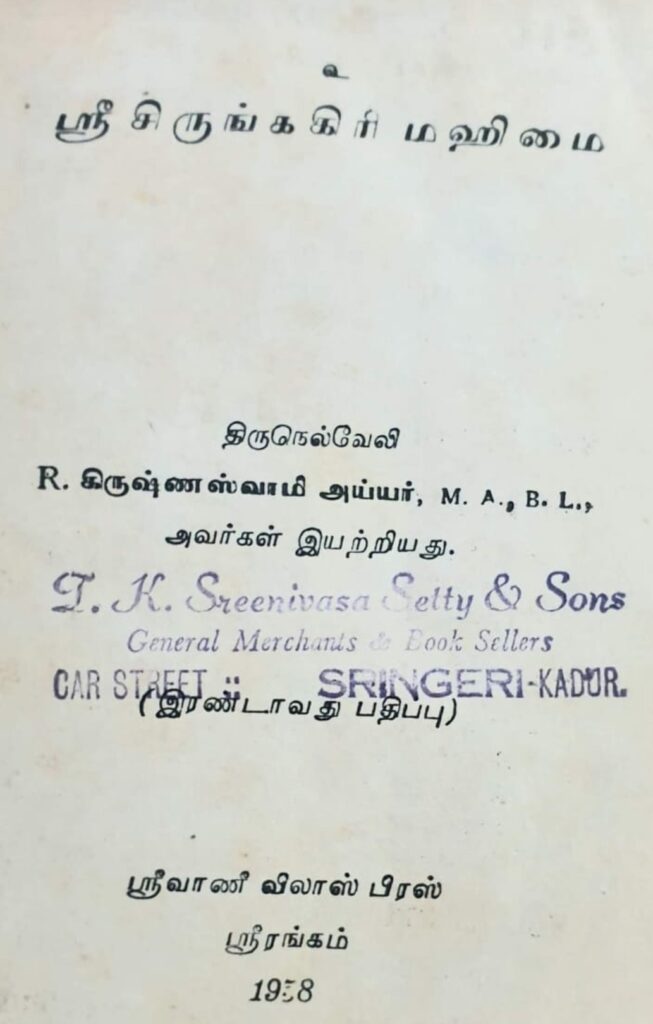

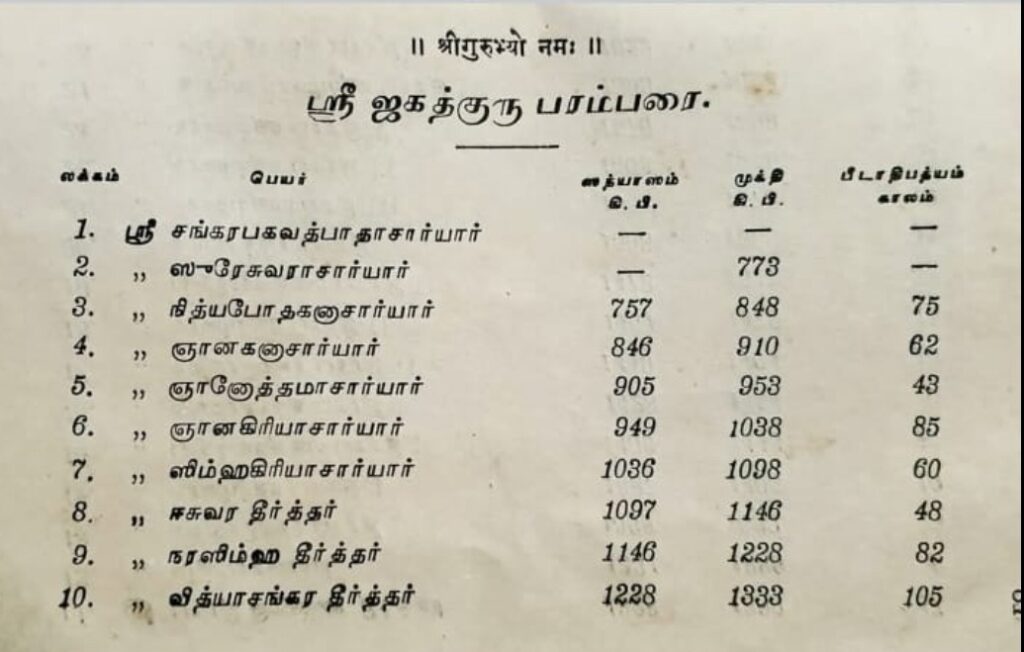

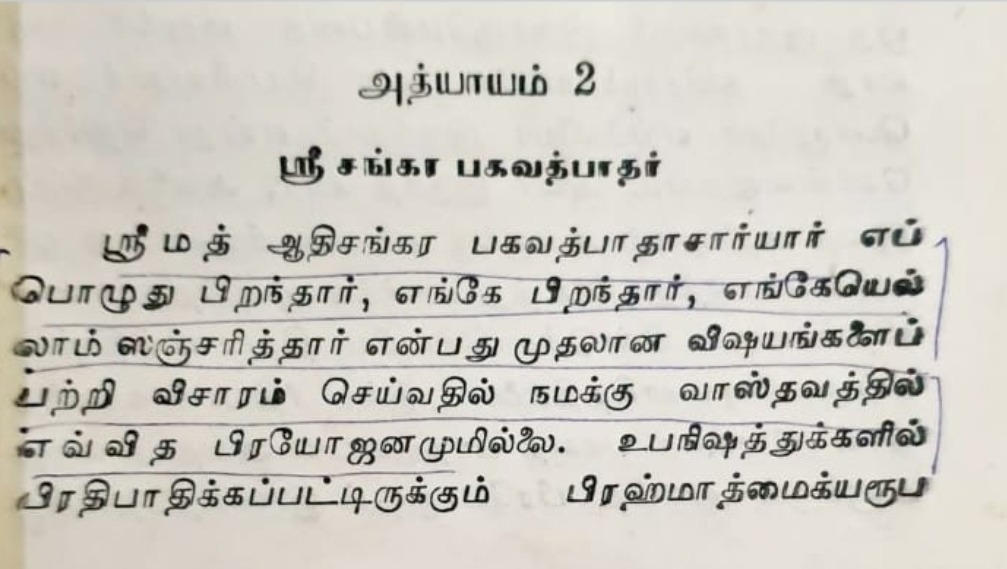

Advent of Shankaracharya : Tunga Adherents’ uncertainty in 1958 & Advocate Krishnaswamy Iyer’s Admission

In 1958, Advocate Krishnaswamy Iyer, Tirunelveli, a staunch adherent of Tunga matha in his book published by the Srirangam Vani Vilas Press, reveals that even at that time, they lacked clarity about Shri Shankaracharya’s birth year, His establishment of four mathas, or Kedara as His place of Siddhi. Iyer justifies the absence of evidence, dismissing such debates as unproductive.This prompts the question: how, why and when were their baseless theories- 788 as His Birth year, the founding of only 4 mathas and kedara as his place of siddhi – systematically planted and propagated by the adherents of Tunga Matha when they themselves were not aware of thse details even in 1958?

Why is Sringeri So called?

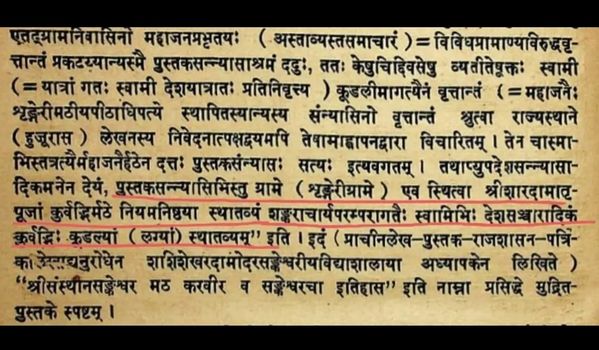

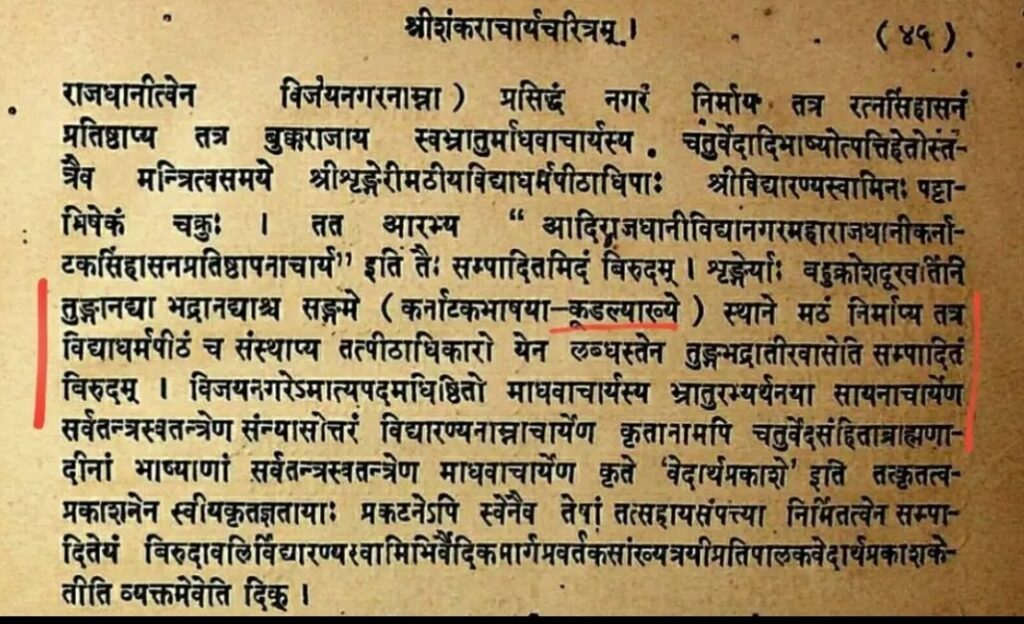

“Why is Sringeri So called?”In Karnataka, many sacred places bear the suffix Sringeri with their name. This name has its origin from Sage Rishyasringa, who performed tapas in the Kudali Kshetra, situated at the confluence of the Tunga and Bhadra rivers. Ancient Inscriptions of Karnataka, studied by B.L.Rice and others, reveal that the sacred hill emerged at this spot due to his intense penance was revered as “Sringa-Giri” in his honor. Over time, the place became known as “Kudali Sringeri”.Source: Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol VI, Inscriptions of Kadur District By B.Lewis Rice, Mysore Government Central Press, Bangalore (1901).

King Sahu’s Intervention to Resolve Spiritual Jurisdiction Disputes Among Kudali, Shankeshvara, and Tunga Mathas (1725 C.E.)

In 1725 C.E., during the reign of King Sahu in the Maratha country, the Swamis of Kudali, Shankeshvara, and Tunga Mathas visited Satara at the king’s invitation in order to resolve their dispute regarding their spiritual jurisdictions amicably. In this important meeting, with the unanimous consent of the Acharyas of Kudali, Shankeshvara, and Tunga Mathas, King Sahu allocated the territories: the northern regions were assigned to Shankeshvara Matha, the southern regions to Kudali Matha, and the Tunga Matha was entrusted with the worship of Shri Sharadamba at their location. Notably, there was no mention of modern texts like the Mathamnaya or Madhaviya during their discussion. This confirms that such ideas were promoted only at a later time.(Sources: History of Sankesvara Mutt, Article published in Indian Patriot, April -June 1912 & Sringeri Matt (Its History) published by (Aviccinna?) Kudali mutt)

Save Mathas from Takeover

Historical records show that the Kudali Sringeri, Shivaganga, Avani and Hariharapura mathas are independent religious institutions and not branches of any other matha. The unique traditions, religious practices and denominational autonomy of the ancient advaitic religious institutions of Southern India should not be overridden by the mere nomination of a successor or otherwise by another matha. Those who attempt to usurp or interfere with their autonomy by any of these modes should know that corporate-style mergers, acquisitions and takeover have no place here.

FAQs: Why Tunga matha should not claim supremacy?

Q: Why Tunga Mutt In Karnataka Should Not Claim Supremacy Over Other Shankarite Institutions?

A: There had been several historical disputes where the Tunga Math in Karnataka, a monastic institution associated with the Advaita Vedanta tradition and Shri Vidyaranya Swami, sought to assert its supremacy over Moolamnaya Kanchi Math, Dakshinamnnaya Kudali Math and other Shankarite institutions.

1. Tunga Math vs. Kudali Math: In the 19th century, Tunga Math claimed Kudali Math as its branch and sought legal restrictions on the Dakshinamnaya Kudali Math’s rights. However, courts consistently ruled Kudali Math as independent Shankarite institution, allowing it to retain its distinct honors.

2. Tunga Math vs. Kanchi Math: Tunga Math tried asserting privileges over the Kanchi Kamakoti Math, established by Shri Shankara Bhavatpada, including rights to repair the Shrichakra Tatankas in the Jambukeshwaram Temple etc. The courts repeatedly dismissed Tunga math’s claims, upholding Moolamnaya Kanchi Math’s traditional rights, independent status and supremacy over Tunga Math.

3. Tunga Math vs. Shivaganga Math: Both institutions approached the Mysore Maharaja in 1831 to resolve disputes over privileges. It was finally decided that Shivaganga Math held equal rights, effectively denying Tunga’s claim to superiority.

4. Tunga Math vs. Virupaksha Math: During the 19th centiry, the Tunga Math attempted to curb the activities of Virupakasha Math.The Nizam’s High Court dismissed Tunga Math”s claims, affirming Virupaksha Math’s traditional rights to function as independent Shankarite institution.

In all these instances, Tunga Math’s attempts to claim dominance were legally challenged and defeated by the Kanchi, Kudali and other maths whose ancient records proved their independence and distinct privileges throughout history.

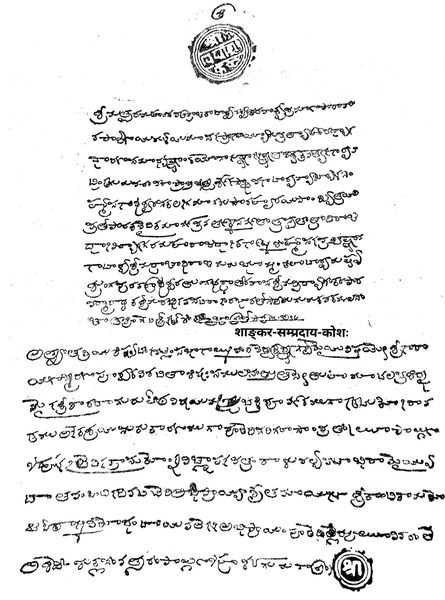

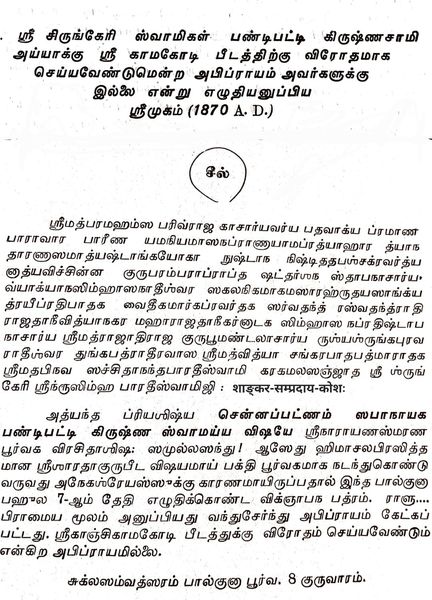

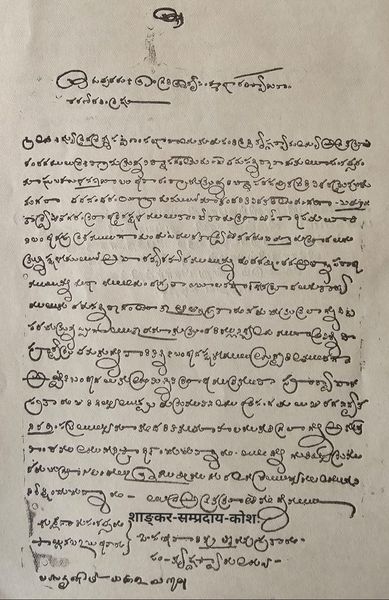

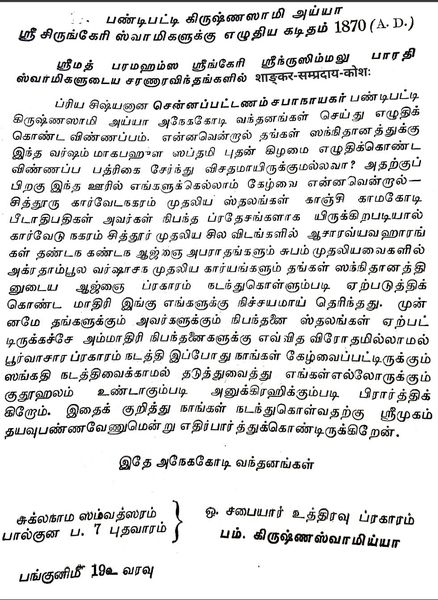

New light on the visit of Tunga Sringeri Acharya to Kanchi in 1871 : (Part-II)

In 1871, the Tunga Sringeri Acharyas visited Kanchipuram to have darshan of Shri Kamakshi Ambal and Shri Shankara Bhagavatpadacharya.

Following the divine orders of Shri Ilayathangudi Perivaa, the 65th Acharya of the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetha, who was also the Adheena Paramparai Dharmakarta of Sri Kamakshi Ambal Devasthanam, the visiting Swamis were warmly received by the officials.

Shri Narasimha Bharathi Swami and Shri Shivabhinava Narasimha Bharathi Swami, first worshipped Shri Adi Shankaracharya (Guru Swamigal ) and offered Swarna Rudraksha mala, Silk Shawl, Kashaya vastra and a danda. The Devasthanam officials also made necessary arrangements for their darshan of Shri Kamakshi Ambal and Shri Adi Shankaracharya (Guru Swamigal) on two days.

This incident highlights the mutual respect and cordial relationship even amidst the legal disputes initiated by the Tunga Sringeri matha and the Kanchi matha’s consistent victories in all cases filed against them since 1835 C.E. (2/2)

New light on the visit of Tunga Sringeri Acharya to Kanchi in 1871 : (Part-I)

Shankarite Institutions across the country were established at various times. Each had its jurisdiction, its disciples and its sampradaya and being Parivrajakacharyas travel was common.

However a vyavastha or maryada was maintained by Institutions on travel routes, shishyarjanam, Agra Sambhavana, pada puja etc. Institutions abided by these rules and records of Kings orders respecting these vyavasthas and cordial relationship was maintained.

From early 19th century, numerous court cases and proceedings arose against the Kanchi Kamakoti matha with the Tunga Sringeri matha as the plaintiff.

In 1870, during the reign of Shri Sudarshana Mahadevendra Saraswati Swami ( Shri Ilayathangudi Perivaa), the 65th Acharya of Kanchi Kamakoti Peetha, attempts were made to collect Agra Sambhavana and intervene in Achara vyavahara matters by the Tunga Matha in the North Arcot and Chithur region.

To address concerns arising from these unprecedented actions against the Kanchi matha, Shri Krishnaswamy Ayya, the Sabhanayaka of Channapatnam (Madras) wrote to the Tunga Sringeri Swami, requesting his Srimukham to adhere to the nibandhanas or traditional restrictions that had been in place in favor of Kanchi matha and maintain harmony in the region.

Shri Narasimha Bharathi Swami, the Tunga Sringeri Acharya also issued his Srimukham, clarifying that there was no intention to incite hostility against the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetha. (1/2)

ஸ்ரீமுக முத்ரை மற்றும் பிருதாவளி ..2..

ச்ருங்கேரி என்ற பெயரொட்டுடன் திகழும் பல்வேறு மடங்களின் ஸ்ரீமுக முத்ரை மற்றும் பிருதாவளி பற்றிய ஆய்வுக் குறிப்புகள் …2

ஸ்ரீவிரூபாக்ஷ மடாதிபர்களின் ஸ்ரீமுக முத்ரை – பிருதாவளி இங்கு தரப்படுகிறது.

(அ) வட்டத்துள் வட்டமான புஷ்ப முத்ரையிலுள்ள சொற்கள்:-

“ஸ்ரீவித்யாரண்ய ஸ்வாமீ”

“ஸ்ரீவித்யாசங்கர மஹீபால முத்ரா”

இதிற் காணும் பிருதங்களில் முக்ய சிலவற்றின் பொருள்:-

“வ்யாக்யான ஸிம்ஹாஸனாதிபரும், கர்நாடக ஸிம்ஹாஸனத்தை நிறுவிய, துங்கபத்ராதீரவாஸியான ச்ருங்ககிரி விரூபாக்ஷ ஸ்ரீ வித்யாசங்கர தேவரின் பாதத்தாமரைகளை ஆராதிப்பவருமான “

Number of Mathas

Q: According to Anandagiri Shankaravijaya, Guruvamsa Kavya of Tunga Sringeri matha, and Kerala Tradition, How many Mathas did Shri Shankara Bhagavatpada establish?

A: FIVE